- Writing style

- Using signatures

- Using rules

- Hidden information

Writing Style

In recent years emails have become an accepted form of communication for business purposes. Previously they tended to be a more informal means of contact between friends. It is therefore important these days to adapt your style of writing according to the recipient. Emails of a formal nature will tend to avoid over friendly expressions and might include a respectful salutation (Dear Sir or Madam for example). Similarly, it is usual to conclude your email with a more formal wording. Always remember the grammatical rule that Dear Sir/Madam requires Yours faithfully (f for formal) whilst Dear John would normally be signed off as Yours sincerely (s for social).

It is important to distinguish between emails and texting. Messaging by text is now extremely common and quick (indeed the younger generation often tend to scorn the use of emailing). Texts have become the repository of a whole new lexicon of abbreviations, phrases and linguistic shorthand. Many examples nowadays require the assistance of a younger interpreter! As a general rule, it is less appropriate to use text language in an email – although even this norm is flouted today between friends.

The whole point about communication is to make oneself understood and people are far less irritated by poor grammar and language than they used to be. Do bear in mind, however, that poor spelling and punctuation can say a lot about the writer if you wish to convey an impression of maturity and learning – in’it!

Using Signatures

One option available in emailing is the ability to append a standard signature block at the end of the message. These tend to be restricted to more formal situations such as when communicating with a customer or business. The signature block can be a couple of lines (Yours faithfully – John Smith) or (as is very common now on emails from businesses and public bodies) a standard form of wording relating to copyright, legal liability and so on.

Having this information previously set up as a signature block pre-empts the need to type in the same wording each time. It is very much like having pre-printed stationery. Here is an example that I use for emails connected to my main website.

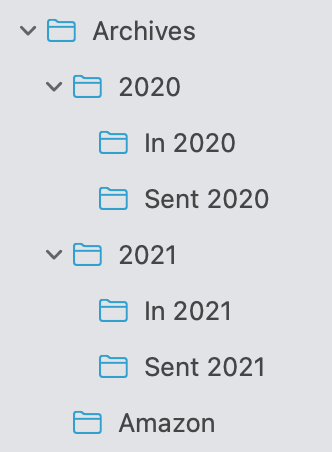

Using Rules

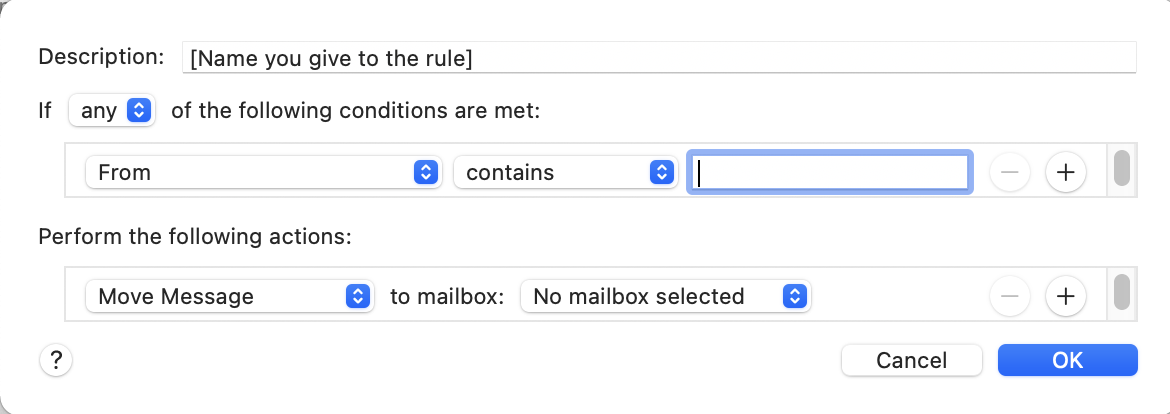

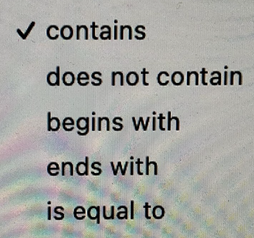

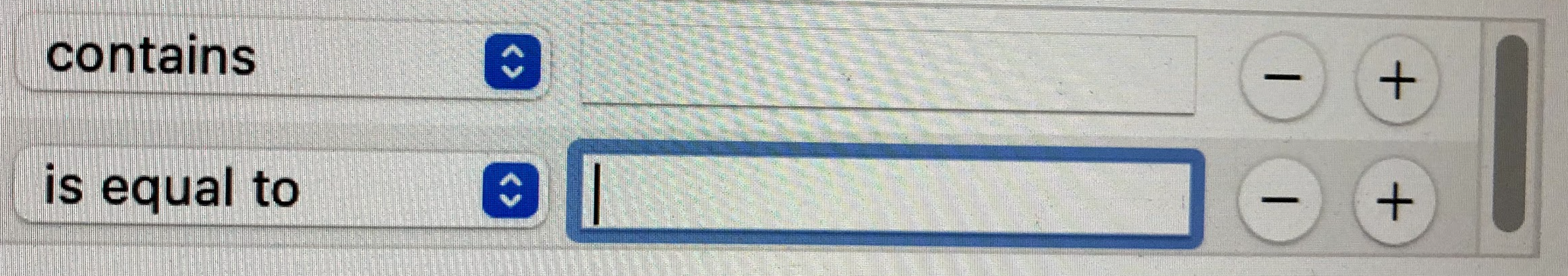

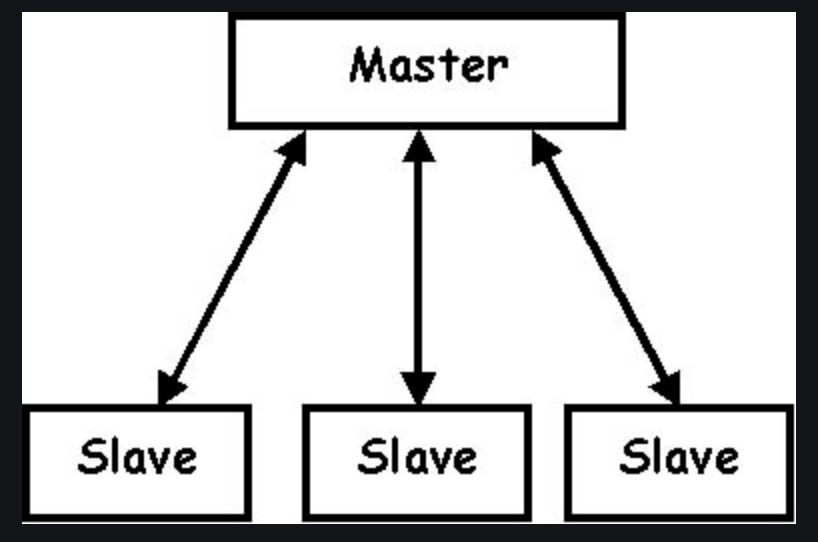

Another feature in all email packages is the ability to create what is called a ‘Rule’ (sometimes referred to as a ‘Filter’). A Rule can be very useful if you want to apply a certain action or sequence of actions to a given message you have received. The standard format for a rule is something like ‘If X occurs then Do Y’. This is best understood by looking at an example of the rule dialogue box (this is from Apple Mail on my iMac).

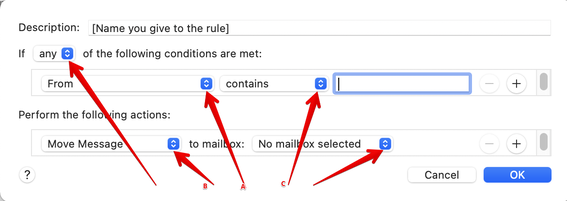

Note that there are options indicated by the blue double-headed arrows. Below I explain three of them.

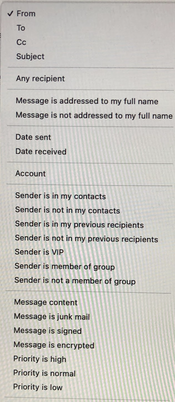

Clicking on any of these arrows opens up a choice. Here is a screen shot of the choices when clicking on the box currently saying From (A):

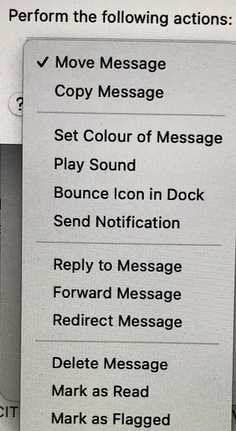

Here is a screen shot of the choices under the Perform the following actions box currently saying Move Message (B):

Here is a screen shot of the choices under the main Conditions box currently saying Contains(C)

As you can see, the options are quite numerous. Once you have devised a rule and given it a name you can invoke it at any time by selecting the name you have given it from the list of rules. (Follow the guidance in your own email package on how to set and invoke rules.)

Hidden Information

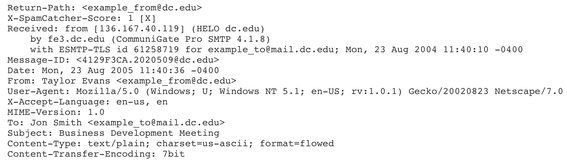

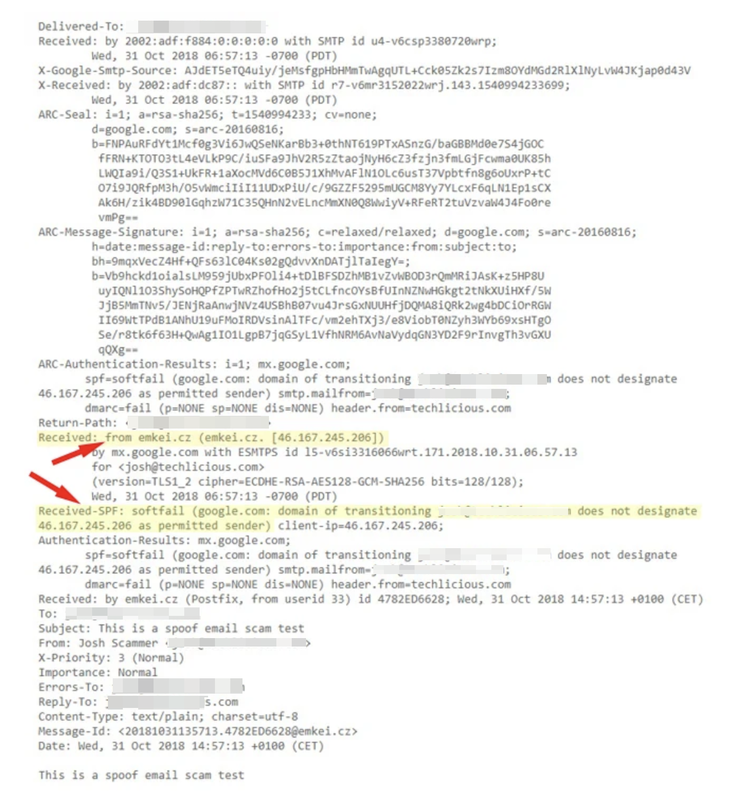

In Part 1 of these articles about emails, I offered an analogy of how emails work – relating them to the passage of a handwritten letter from sender to recipient via the post office. I said that an email – just like its physical counterpart – was enclosed in an ‘envelope’. This is called the “Header” and it is hidden from the user unless you know how to access it.

The header of an email contains all the necessary information that computers in the chain from sender to receiver need to know to enable it to reach its destination. This includes the internet addresses and identities of sender and receiver; the route that the email takes on its journey; the various software packages involved in its journey; all the intermediate ‘stops’ the message passes through (each of these stops is called a Message Transfer Agent [MTA] and has its own identity); any special instructions about how the message is encoded; authentication data (to prove the validity of the message); the time and date ‘stamps’; and other information to enable the message to be tracked on its route. Here is an example of a simple email header: (all details are fictitious)

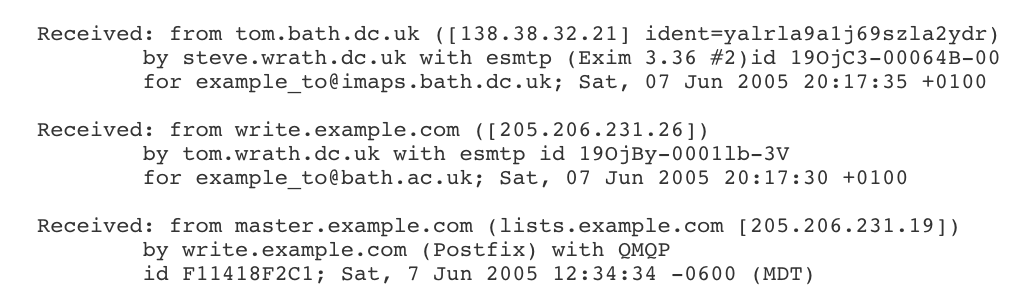

Very often the header is much longer and contains detailed information about the email's journey around the internet. Here is an extract from a header where the email passes through three MTAs (intermediate stops).

Although you do NOT need to worry about trying to understand it, this last picture is included to show that delving deep into the email header can enable you to find out if the sender is legitimate or not. It is taken from a live example from the internet so actual user's name has been obscured). The wording of the header detail is difficult to read but the key parts are shown by the arrows.