Note for Computer Experts! The description that follows is a very simplified explanation of the workings of a computer. It is not intended to be a definitive or exhaustive account, is not meant as a textbook and probably has more holes than a block of Gruyere cheese. E&OE (Errors and omissions Excepted) as they say in legal contracts.

This post seeks to explain the basics of computer workings and how they rely upon a set of instructions (a programme) to carry out a particular task or tasks. Remember the earlier description of the Jacquard Loom and how different cloth patterns could be produced using a different punched card for each pattern? In this instance, the operation of the loom was mechanical - a hole in the punched card corresponding to a lever which was activated as the card passed through the loom. The card's passage through the loom was controlled by turning a wheel using a handle or foot pedal. Later models provided power by an engine which worked either by fuel or electricity. Essentially however, the machines were still analogue whereby a physical action created a machine response.

As we progressed into the 20th century we saw the introduction of electrical impulses to trigger certain actions in a computer. Unlike the earlier mechanical calculators (controlled by hand, foot or even electricity turning cogs or levers), an electronic computer works in a fundamentally different way. Here, a power source in the form of a spark of electricity creates a direct response from a component in the computer. To understand the principle think of a light switch which, when pressed, lets electricity flow that then causes the light bulb to light up. The light is said to be ON. Switch again and the light goes out and is said to be OFF.

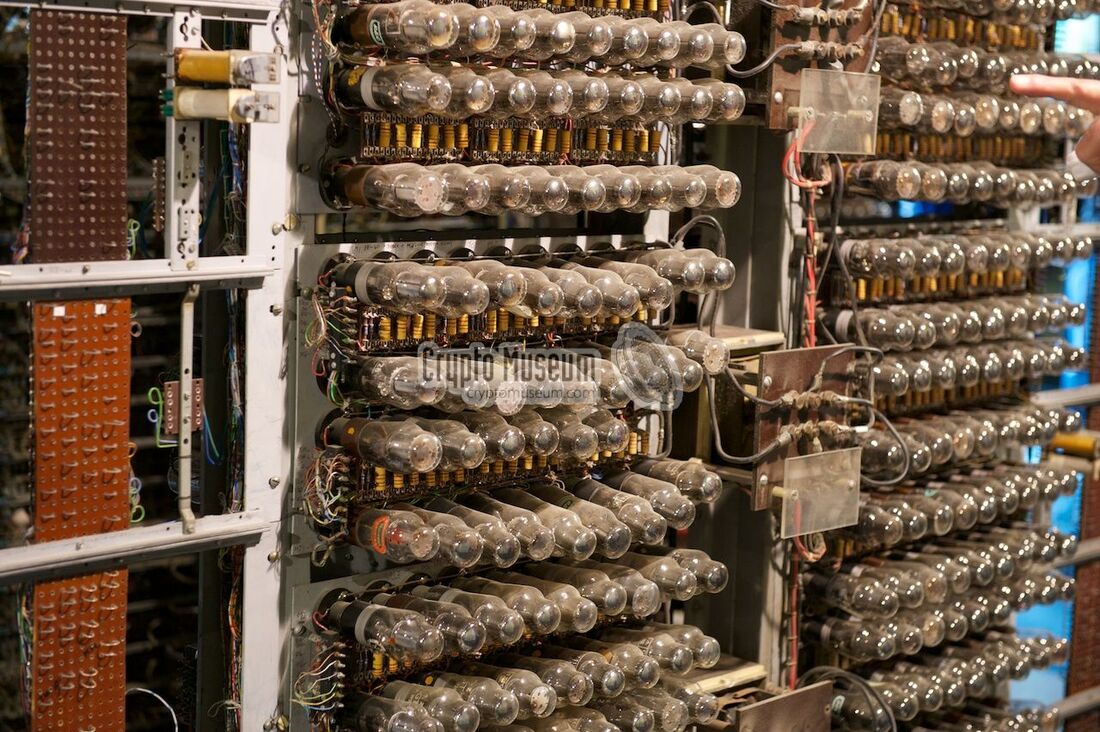

Now imagine the computer is a box full of light bulbs each controlled by a switch. By depressing the switches you can light up the bulbs in any order you wish. The earliest electronic computers were essentially just this except that instead of light bulbs the computer held valves that lit up. In my earlier history I spoke of the first large computer called Colossus. Here is a picture of it showing the valves (photo by courtesy of the Crypto Museum).

There now follows a light bulb moment.

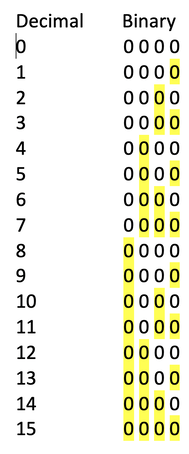

Okay, so that's alright for numbers but how does a computer store letters (A, B, C....)? This is made possible because we can use a separate code where certain binary numbers can also represent alphabetic letters. This code is called ASCII code which stands for American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) and it has been around since 1963. Thus the binary number 01000001 (which is 65) can also be read by a computer as the upper case letter A. Hopefully you can see that to create a string of letters the computer actually stores a series of numbers representing those letters. Lesson Over! If you wish to know more about the ASCII code you can go to this Wikipedia article.

Programming

The next stage in telling you how computers work is to look at the role of programming. However, we'll leave that for the next article.